In February, Great Neck Public Schools welcomed guest speaker Martin Luther King III in honor of Martin Luther King Jr. Day. While well-intentioned and appreciated, the event’s parting message ultimately boiled down the complex issue of anti-discrimination to the simplified solution of “treating each other with kindness.” Given the maturity level and unique demographic of South High, this surface-level sentiment failed to address the deep-seated realities of racial injustice that affect marginalized communities. It prompted me to reflect on how we, as students, can engage in meaningful conversations about race and activism, all while considering the context of our identities. With May marking Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, we have an opportunity to examine how AAPI narratives are understood—not just by others, but by ourselves.

Unlike most schools in the United States, Great Neck South is in the rare position of being home to a large, generally privileged, and high-achieving Asian American population. Many of us refer to the comfort and security we experience as the “South Bubble”; however, this bubble also shields us from the overt racism others elsewhere face daily. In turn, we can be dismissive of the subtle, internalized manifestations of discrimination that exist within our classrooms, families, and even our own hearts.

A glaring example is in how school curriculums approach Asian American history. We may have learned about the internment of Japanese Americans or the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, but this is often where the discussion ends. In fact, much of the condensed and time-constrained content we are taught is rooted in the oppression of Asian Americans, overshadowing the incredible achievements and contributions of the AAPI community. The lack of a comprehensive approach to AAPI history leaves many of us left out—and, subsequently, unaware—of the nuanced legacy we are preceded by.

Compounding this issue is the myth of the model minority. While the “successful and hardworking” image may seem flattering on the surface, it reinforces a stereotype that reduces the vast diversity of those under the AAPI umbrella into a picture of homogeneity. This flattening disempowers Asian Americans into a monolith that can be easily molded and digested into a “single story,” which proves dangerous when it sidelines AAPI voices as a footnote in the broader conversation about race and representation.

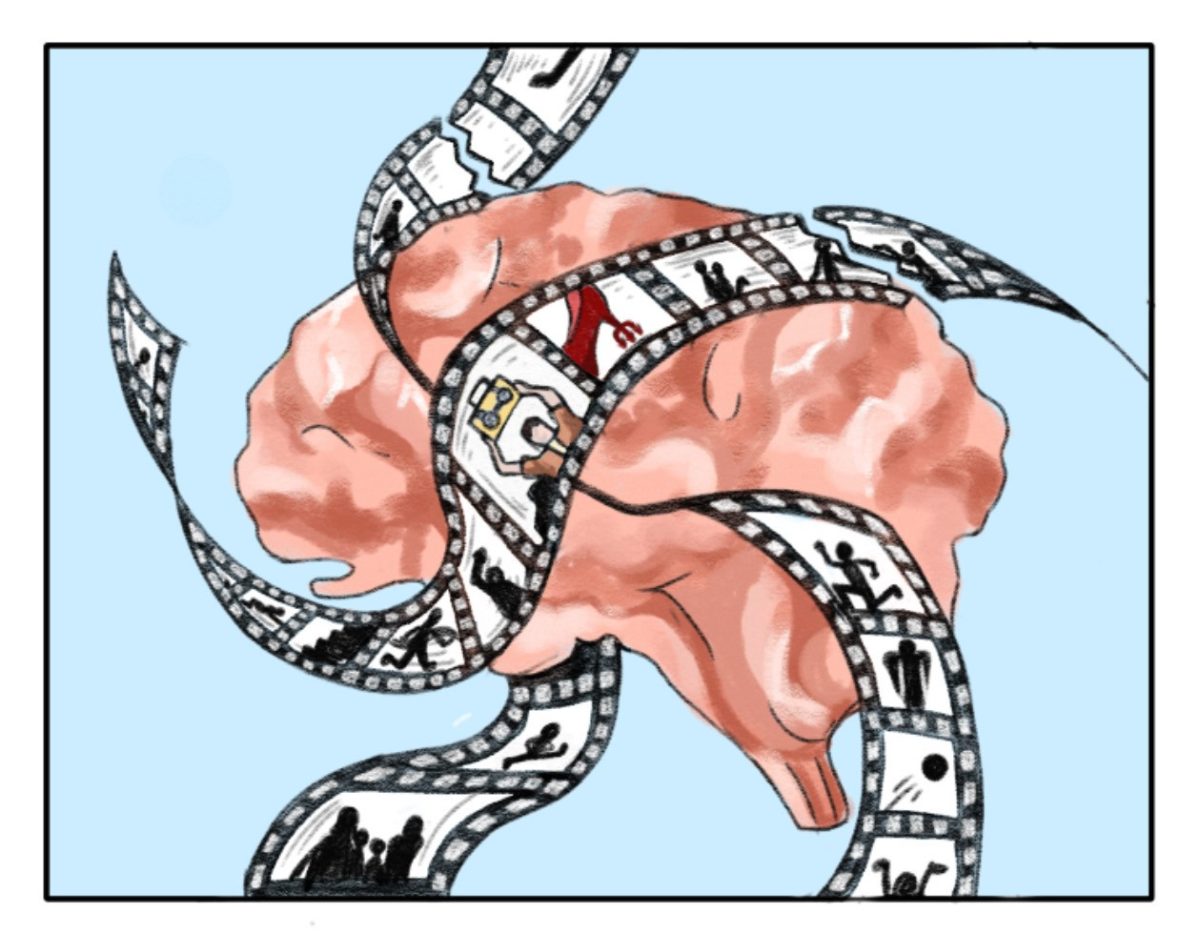

But this issue runs deeper than external factors; there is also an internal disconnect within the AAPI community itself. Unlike other marginalized groups, AAPI movements are often fractured and muted, stemming from a history of disunity among those under the umbrella. Alongside the effects of ignorance and erasure, it becomes challenging to cultivate a solidary voice strong enough to challenge systemic injustice. To bridge the gap left by limited curriculums, pervasive stereotyping, and collective disjointness, it is essential that we take responsibility for our own education by engaging with stories that challenge the perception about who we are. One of the most accessible and powerful ways to do so is through literature. We all know Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club, but there are thousands of equally compelling works that offer rich counter-narratives defying the monolithic erasure of AAPI diversity. Whether through fiction, memoir, or essay, such literature allows us to hear lived-in experiences of Asian Americans that reflect the true breadth of our community.

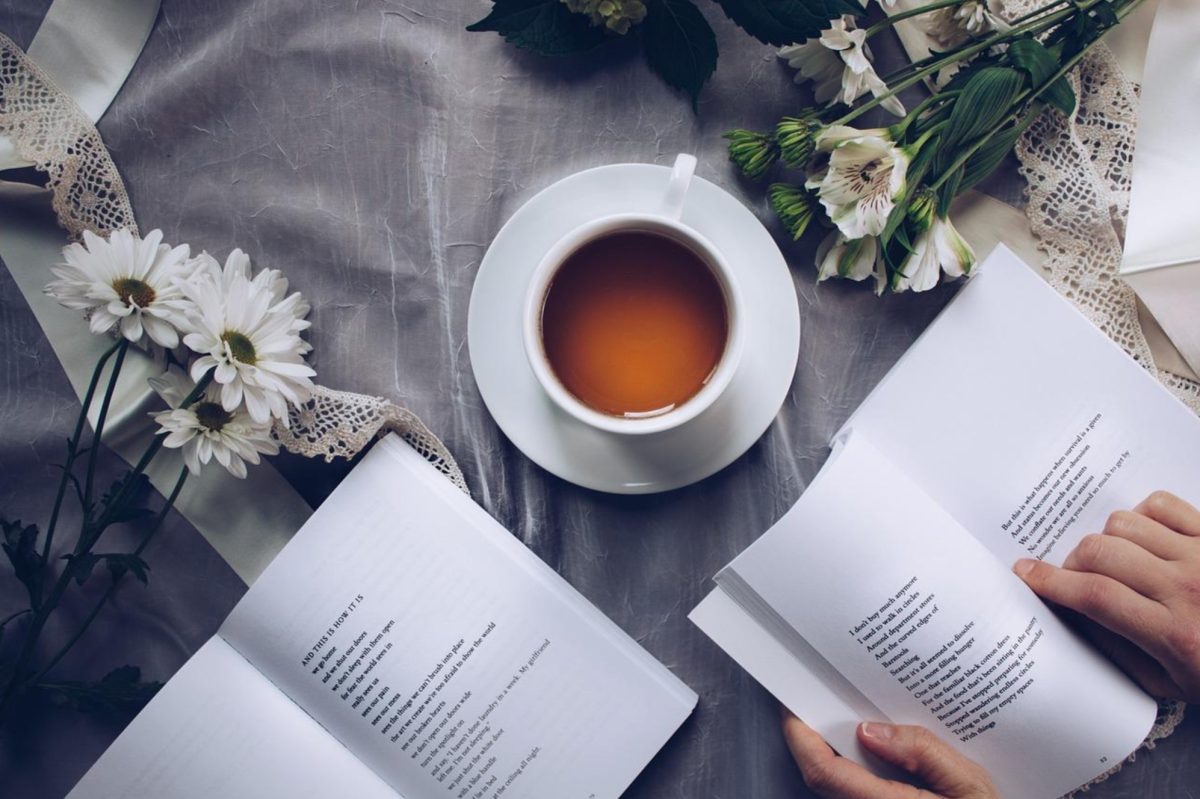

For me, intentionally reading AAPI literature transformed my connection with myself and my peers. I had assumed that because I was Asian American, I knew the story of my people and should utilize my time learning about other marginalized groups. However, reading the nostalgic fragments of Ocean Vuong’s poetry or the raw honesty behind Prachi Gupta’s memoir made me confront uncomfortable truths about how I had internalized stereotypes and distanced myself from others in my own community. To be seen so explicitly on paper when my identity seemed so often overlooked was an act of empowerment I hadn’t realized I was missing. These stories were not simply representations of personal struggles or triumphs either; they became foundations to developing a stronger, more accepting identity that I—like many of us—felt removed from.

In our “South Bubble,” it is easy to feel disconnected from the broader AAPI experience. But actively seeking out counter-narratives can dismantle the insular mindset that prevents us from fully hearing and appreciating the depth of the AAPI voice, and by extension, our own. Only then can we start to advocate for a more just and unified future without the dangers of a single story.