Today, we often hear politicians bemoan political correctness—right before saying something that people may find insensitive, disagreeable, or prejudiced. Political correctness is simply the active attempt to avoid language that marginalizes or discriminates, yet people have ascribed a negative connotation to the concept when they conflate censorship with this correctness. But the core of the issue concerns labels, how we classify, distinguish, and differentiate. The intention behind labeling is to create some basis or standard by which we categorize things. If the issue regarding labels is pigeonholing, the obvious first solution is to stop labeling, but such an idea is vastly impractical, as that would require doing away with just about all titles and names, all things that we depend on in our everyday lives. The second more plausible solution lies in being aware of labels and their effects. If we cannot eradicate labels, we can at least strive to control them and regulate the effect that they inevitably have on all of us.

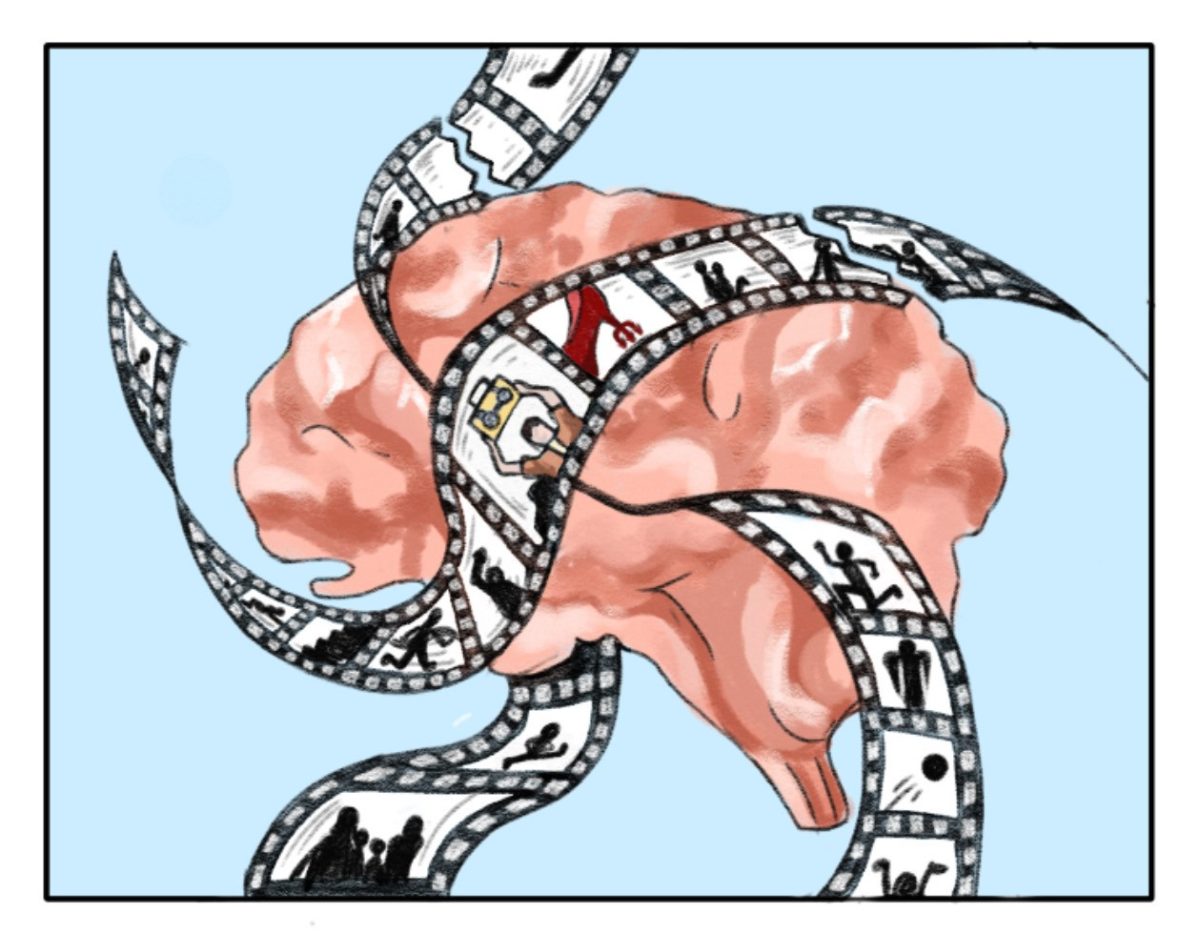

Because we can marginalize and even relegate those whom we distinguish with labels, our usage of unbiased labels can be conducive to a more inclusive and egalitarian society. Generally, when we describe people, these people, regardless of the validity of our description, absorb our perceptions into their own sense of self. “Labeling theory,” a sociological concept, says that terms used to describe or classify can affect or even control the individuals being described or classified. George Herbert Mead, an American philosopher, sociologist, and psychologist, postulated a similar idea conveying the power of words and labels. He posited that individuals create their respective self-images based upon what they interpret as others’ perceptions. In simpler terms, we construct our ideas of ourselves based on what we think other people perceive us as.

In a 2012 study by the American Psychological Association (APA), an experiment indicated that attribution, ascribing a trait or inclination to a child’s character, is more effective than reinforcement, praising a child for doing a certain action. In the study, children who showed magnanimity were split into two groups: one that was praised for generous behavior/action and another that was praised for generous character. Children who were told, “You’re a helpful person” were more likely to be more generous weeks later than those who were told, “That was such a helpful thing to do.” The existence of such effects on our outward projection is what makes labeling potentially dangerous in society. In order to create an inclusive and unrestricting environment, we should be consciously aware of our word choices and the way they could potentially affect others.

Similarly, persons described by labels may attach the label and its underlying meaning and connotations to their identities. While it may seem benign or humorous, labeling a peer a “nerd,” for example, could potentially cause this person to see and restrict him or herself through the lens of this characterization. In labeling a person or group, we limit not only our perception but also the person or group’s identity, which was otherwise to be self-determined. According to Robert Merton in an article published in The Antioch Review, this phenomenon manifests in the behavioral concept of a “self-fulfilling prophecy,” a definition, false or partially true, that evokes new behavior that renders the original false or partially true conception true. The power of labels, of mislabeling, could potentially lead to individuals even conforming to said labels, and the sheer influence of this possibility should be enough to compel us to be careful with the assignment of labels and the language of such labels.

Given the effects of biased language, there is clear and moral need to expunge it from society’s collective consciousness. We can’t completely remove labels from society, but we can do our best to limit the harmful effect labels can have. Because this must be a collective effort, we must be aware of not only our own usage of labels but also that of others. Promoting awareness can be as simple as politely informing others that they are using a term that a certain group of people, perhaps a group they know little about, might be harmed by the continued use of said language. This will also mean listening to others with an open mind when they inform you of how your own speech might be affecting others. Of course, the words we consider harmful and offensive are determined by society’s idea of morality at any time. This phenomenon requires that we constantly reevaluate labels and observe their effects.

To be clear, this sensitivity to the way our vocabulary inherently affects others does not inure groupthink or limit free speech. A person can still communicate whatever he or she likes, yet his or her communication alone won’t perpetuate harm unto others.

The inherent bias of our language and our tendency to label is almost inescapable. However, there is clear danger in our unbridled use of labels, pertaining to not just the nature of our labels but also the effect of such labels. Striving to use unbiased labels can help make our society a more impartial and equitable one.

Categories:

Our Liability for Our Labels: Be Wary of How We Categorize

May 26, 2016

Cartoon by Angelina Wang

0

More to Discover