During the 1950s, many believed that women could only find fulfillment through childbearing and homemaking. However, many women were secretly unhappy with their roles as suburban housewives. Inundated with images of happy housewives in magazines, television, and the radio, they thought that they were the only ones dissatisfied with their lives and, as a result, questioned what could be wrong with them.

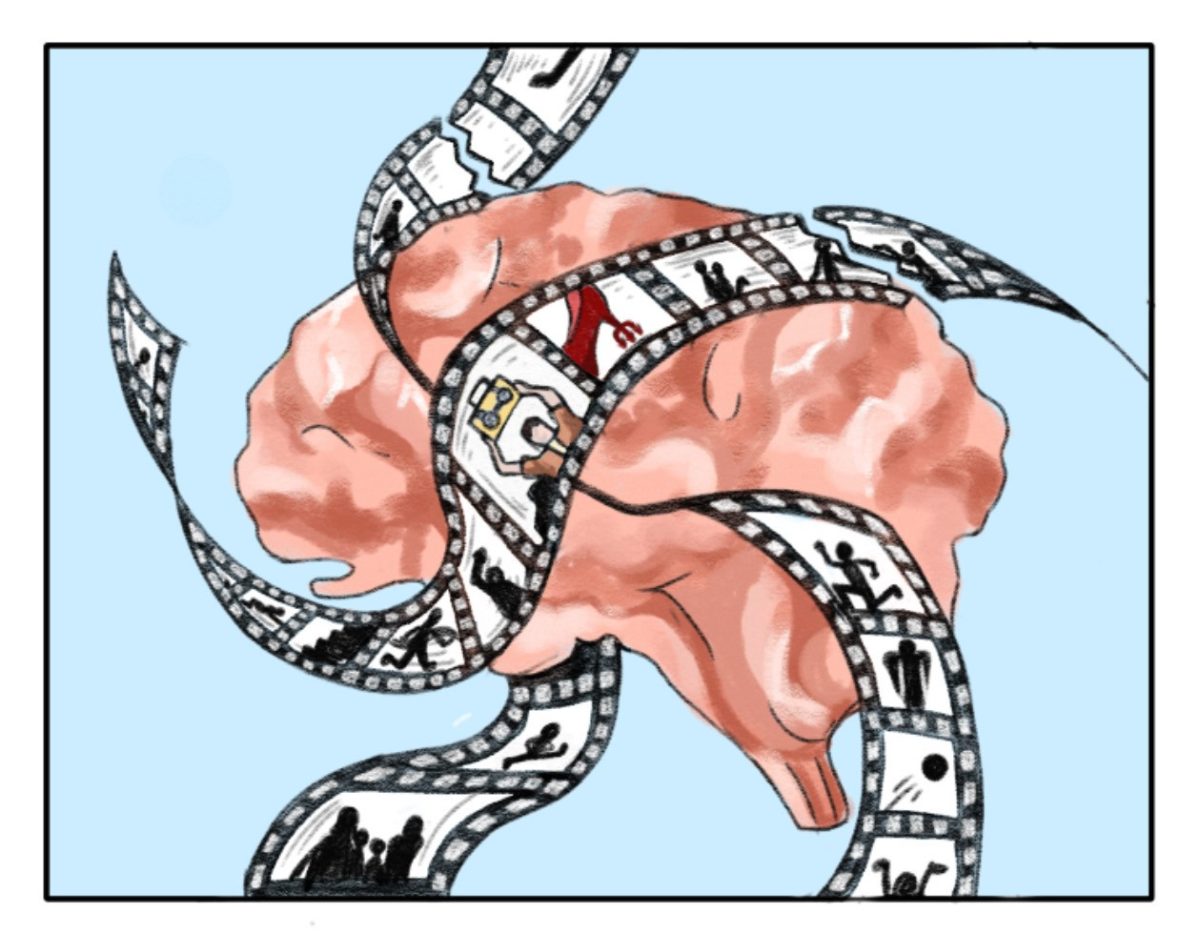

Almost 70 years later, we face a similar problem. Today, many people post pictures of themselves and their lifestyles in an effort to uphold an ideal image. These perfect pictures leave many wondering why their own lives aren’t as flawless as the ones found on their feeds. In fact, researchers found that one-third of people feel lonely and dissatisfied after scrolling through their Facebook feeds.

In 2012, Mark Zuckerberg, creator of Facebook, wrote that social media was “built to accomplish a social mission—to make the world more open and connected.” While there is no doubt that we are now more connected, are we really more open?

After teeth-whitening and lighting adjustments—and of course a punny caption—our posts are ready to be shared with the world. But, after all the edits, do the pictures still reflect who we are?

In a way, we are like Perry the Platypus and Hannah Montana. While, no, we don’t spend our spare time as a secret agent or pop star, we do live a double life: our virtual identity is significantly different from our real one. Social media creates an illusion of perfection. It encourages us to put a filter on our lives and only show what we want others to see. It’s artificial. It’s superficial. It’s, simply put, not real.

When we are engaged in a fun or interesting activity, we take selfies instead of living in the moment. Some even go so far to say that we go to cool places not for ourselves but for Instagram. From a young age we were taught that sharing is caring, but sharing becomes a lot less caring when we are only doing it for our own benefit: We seek validation; we seek likes.

A single like offers immediate gratification. The more likes we get on our post, the more dopamine released. But what’s really interesting is that our bodies release the most dopamine right before we post the picture—in anticipation of the likes. That means that we don’t just enjoy getting likes; we crave them. The even bigger problem is that each like validates our misplaced value on our virtual image, and therefore, validates our behavior. From this standpoint, it makes sense that we tend to hide our flaws on social media.

Finstas, however, allow us to embrace the imperfect parts of life. While finstagrams are supposedly “Fake Instagrams,” they are the most real thing that can be found on any social media app. With a quick, haphazard photo and a matching caption revealing our obsessions with our pets or our altercations with our parents, the filters—literally and figuratively—are removed, and for once we get to see real thoughts, real people.

In order to be true to ourselves, we need to make an effort to share all forms of ourselves on social media, not just on our finstas. Life is sometimes boring, basic, dark, messy, and ugly. But life is real, and if we can’t share our real selves, then what are we really accomplishing?