Coming Out About the Coming Out Narrative

January 24, 2022

In correspondence with the growth and mainstream acceptance of the LGBTQ community, LGBTQ literature has blossomed in popularity, especially since the 2010s; but as social attitudes towards LGBTQ people have shifted, so has the LGBTQ novel changed with them, for better and for worse. And while this popularity is largely beneficial—an increased exposure and familiarity to lives that are fundamentally different from ours increases our compassion towards others—it comes at the needed cost of authenticity. To reach such levels of mass appeal, this recent iteration of, mostly YA, LGBTQ books has had to focus on the one part of LGBTQ life that does directly affect cis and straight people: coming out.

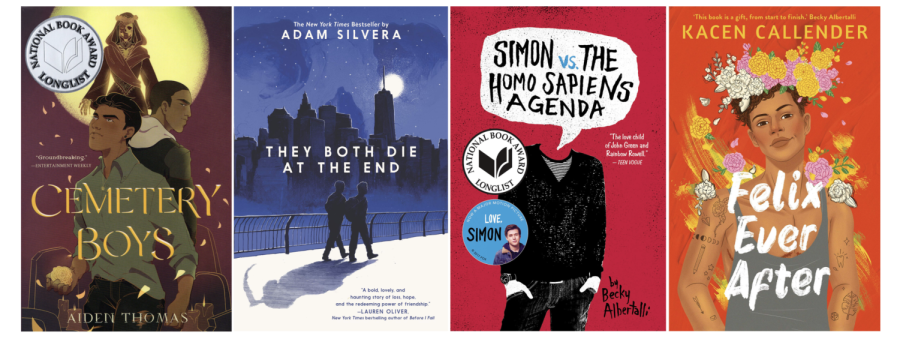

In many respects, this focus on coming out is necessary. Being LGBTQ is simply not an experience that many people can relate to, and it may be hard to feel invested in a struggle that is so far removed from one’s own reality. Focusing on the intersection between gay or trans people and cis and straight people partially solves this problem; it allows cis and straight readers to feel connected to the narrative by centering it around an interaction they will probably experience, while keeping the LGBTQ character at the forefront. And, if the success of Simon Vs. the Homo Sapien’s Agenda and its movie adaptation is anything to go by, this narrative works. A problem arises, however, when this framework, for all its positives, becomes the dominant vehicle in which LGBTQ themes and stories are told to a general audience. By dealing solely with a single, relatable aspect of LGBTQ existence, the “coming out narrative” ends up distilling the vast diversity of LGBTQ life into one storyline, leaving all other experiences to the wayside.

The coming out narrative maintains four key components: firstly, the LGBTQ character the narrative revolves around, secondly, the external motive for coming out, thirdly, the large “coming out scene” that is often the climax of the story or the character’s arc, and lastly, the freedom and joy that accompanies coming out. This narrative often serves as the plot of entire books—such as in I Wish You All the Best by Mason Deaver, which opens and closes with a coming out scene—but it is used as the prominent character arc for LGBTQ secondary characters as well, such as with Nico di Angelo in The House of Hades by Rick Riordan. In both cases, while the stories themselves handle deeper themes with nuance, the almost singular focus of coming out with regards to the LGBTQ characters cheapens them overall. These characters are not allowed depth specifically in regards to their LGBTQ identity outside of the act of coming out, reducing an entire identity to a sole scene.

Of course, coming out is a part of LGBTQ life and it, like all parts of life, has its place in literature. But it is not the only part. Some LGBTQ people—for various cultural, religious, or personal reasons—never come out. Others come out only to their friends, and still others come out in some way every day of their lives. Even within the “coming out experience” there is a great deal of variety, and even more experiences that fall outside it entirely. The focus on coming out in literature is disproportionate to its presence in reality, alienating different, complex narratives. While there was certainly a place for the coming out narrative when LGBTQ literature was first becoming mainstream, there is so much more to being LGBTQ than coming out, and those narratives have a place in literature as well.

And for the most part, these narratives seem to be gaining more widespread recognition. Books like They Both Die at the End by Adam Silvera and Felix Ever After by Kacen Callender, although both contain a coming out scene, have narratives that transcend the limitations of the coming out narrative and deal with LGBTQ identities in a meaningful way outside of coming out. Thankfully, the coming out narrative seems to be waning in abundance—especially with the rise of LGBTQ fantasy, where the homophobia and transphobia that necessitate coming out can no longer exist—and stories are becoming more diverse across the board. But don’t stop reading LGBTQ stories because they contain the coming out narrative. If anything, read more of them! Simply make sure to read other LGBTQ stories as well, and realize that a single narrative will never be enough to represent an entire group.