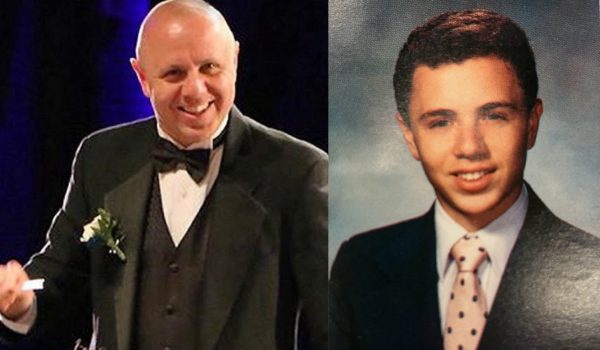

Notable Alumni Interview Series #5: Anoush Baghdassarian

June 23, 2022

Anoush Baghdassarian (Class of ‘13) received her Juris Doctorate from Harvard Law School, her Master’s Degree in Human Rights Studies from Columbia University, and her Bachelor’s Degree in Psychology, Spanish, and Holocaust Studies from Claremont McKenna College. Baghdassarian co-founded Rerooted, an archive documenting the Armenian community of Syria. Baghdassarian received the 2022 Andrew L. Kaufman Pro Bono Award for working an unprecedented 4,000 pro bono, or free-of-charge, hours during her time at Harvard Law School. She will work at the International Criminal Court as an International Legal Studies Fellow and return for a clerkship on the Second Circuit in January 2024.

Sophia Liu: How was your time at Great Neck South High School? When did you attend? What was your most memorable experience?

Anoush Baghdassarian: I attended Great Neck South High School from 2009 to2013. My time there was empowering, and inspiring. I really felt like I was supported by every teacher in every subject, in class and in extra help, to pursue different ideas and extracurriculars. I really thought I got the most out of it that I could.

My most memorable experience would either be being the president of Theater South or writing a play about the Armenian Genocide in Mr. Weinstein’s creative writing class my senior year. I had this idea and he said, “Absolutely, you should do it.” I wrote it all in his class and then I introduced it at LEVELS in the Great Neck Library. I had my friends from Theater South and other theater friends from Great Neck participate in the show, and it was really meaningful.

SL: That was your play, FOUND, right? What inspired you to write the play and why did you choose playwriting as the form to tell this story?

AB: Since fifth grade, I’ve done theater in school. Then in high school, I really immersed myself in the wonderful theater program often interacting with Dr. Levy, Mr. Marr, and Mr. Schwartz. I took a particular liking to acting, over singing or dancing, so I spent my summers in high school going to theater conservatories. I went to Stella Adler, USDAN, and the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. In my last summer before college, I spent a month in England at the British American Drama Academy. I thought theater was very powerful. Theater allows one to bring people into another world and have them empathize with something that they otherwise might not know. Theater can help show you, in a subtle yet powerful way, the shared humanity that you have with somebody else. When you see a character feeling something that you felt, or going through something that you’ve gone through, you recognize the humanity that you have in common. Theater is didactic.

So, I chose playwriting for that reason. I really loved acting, and thus had read so many plays in school and on my own, and the form of it resonated with me; I had a familiarity with it that lent well to trying my hand at one as well Not only through Theater South did I learn of the different powerful forms of theater, but through English classes as well. For example, we read The Crucible in 11th grade in Mr. Graham’s class and I saw how powerful an allegory that was for the Red Scare. I saw in that example how playwriting could be such a powerful way to talk about otherwise taboo topics, which is an important avenue to find particularly when it comes to advancing change for human rights causes. Actually, literary writing and human rights are not so far removed from one another as one might initially think.

I read a book in college by a woman named Lynn Hunt titled Inventing Human Rights that the invention of human rights coincided with the birth of the epistolary novel. Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded is one of the first versions of the epistolary novel in the 1700s. The book is from the point of view of a servant, and so for the first time, the aristocratic classes could read and feel and understand the perspective of a servant whom they otherwise wouldn’t interact with. The aristocracy could start to empathize with the servants and realize that they’re not so different and start to champion human rights. In High School, though I didn’t know of Hunt’s theory, I felt theater had this same power to move people.

SL: Have you pursued playwriting after high school?

AB: In college, I wrote two plays. I double majored in Psychology and Spanish with a Holocaust and genocide studies minor. I wrote the first play about the Israel-Palestine conflict. Then for my second senior thesis, I wrote a play in Spanish about Argentina’s last military dictatorship, in which over 30,000 people ‘disappeared.’

Actually, I studied abroad in Argentina and learned that film played a large role in achieving justice. Movies helped shape public perception and thereby had an indirect effect in helping to repeal the amnesty laws that were in place, which meant that alleged perpetrators wouldn’t be charged or held on trial.

Something I’ve always held to be true and that has been reinforced over the years is that it’s important to be nuanced. I don’t ever make any characters black and white, without nuance. I constantly learned about my own family history in which Turkish neighbors helped some of my family members survive, and I also learned about numerous examples throughout genocides of the 20th century where neighbors killed one another. All of this showed me how thin the line is between ‘good’ and ‘evil’ and I would reflect on the fact that it wasn’t really “history repeating itself” as I had learned in the classroom, but rather, “people repeating history.” I couldn’t understand what allowed people across time and geography to continue perpetrating such atrocities against their neighbors and that is why I majored in psychology to study the psychology of perpetrators and why and how ordinary people could do this over and over again. I learned there are many mechanisms of moral disengagement that help people convince themselves that what they’re doing is okay. For example, there’s dehumanization, in which you start to call the other group the other, or a virus, or a cancer, or a cockroach so that it’s easier to harm them. I think it’s very easy for people to cross that line between being a victim and being a perpetrator. In the play I wrote about Argentina’s dirty war, I built a character to play with the idea of somebody who was both really loved, but also had committed crimes, to explore and expose the human dynamics of ‘good’ and ‘evil’.

SL: Was there a teacher at South that particularly influenced you?

AB: I can’t choose one. I really loved all of my teachers at South. I loved that everyone made time for me—I could go to extra help all the time for any subject and every teacher would be there excited to help me and answer my questions. The math and science teachers would spend so much time with me when I didn’t understand something; math and science were not my forte. My social studies, Spanish, and electives teachers were all great and supportive, as was/is Mr. Erickson, my guidance counselor!

Given my interests and chosen career path, my English teachers were surely influential. Their excitement about the books we read was contagious, and I still remember many of the books and can confidently say the messages they conveyed are still impactful today. Beyond everything I learned from The Crucible, which I mentioned earlier, Mr. Graham gave us wonderful fiction like The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and nonfiction like the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. Importantly, he also taught me not to use “a lot” in formal writing because that’s where we park a car; Beowoulf and Samson Agonistes in Dr. Manuel’s class were powerful pieces of writing that expanded my mind and taste; Of Mice and Men in Ms. Hastings’ class was impactful, as were our Julius Caesar monologues; and in Ms. Sparaccio’s class we read so many great books- Night, The Things They Carried, Great Expectations, Catcher in the Rye, To Kill a Mockingbird…10th grade English class was really a literary goldmine!I was so fortunate to learn from Mr. Amelio as an honorary English teacher, constantly inspired by his playwriting and even fortunate enough to go see one of his plays in Manhattan; and I really just feel incredibly fortunate that I chose to take creative writing with Mr. Weinstein because he was so encouraging and helpful with my play and I am not sure it would have happened without him–without someone to enthusiastically say yes to my hesitant, half-baked idea, and cheer me on every step of the way. That influence is not lost on me and I am eternally grateful. Each of my English teachers, and Mr. Marr, who I know is now an English teacher but who was my biggest teacher and supporter in the theater wing back in my time, gave me such a tremendous foundation for being an empathetic and ethical person through the choices they made in the classroom or on the stage, literature they gave us, and lessons they ensured we took from it, and I treasure my time and relationship with each one of them.

SL: Did you do any clubs or sports outside of theater?

AB: I played soccer my freshman and or sophomore year. I played lacrosse for three years. I was the president of Key Club, and I probably did some other clubs that I can’t remember at this point!

SL: Much of your work centers on your Armenian heritage, on healing and reconciling from the Armenian genocide. How were you initially exposed to your family history and how did it inform your work now?

AB: I think I was initially exposed just by hearing family and community stories growing up I went to Armenian School on Saturdays for a few years and Sunday school until 11th grade.

Something I remember with a smile is that I was constantly asked to explain my name and where it comes from, so I remember I would say, “well, I’m Greek and Egyptian and Uruguayan and Argentinian and American, but really, I’m Armenian. When people were understandably confused, I reiterated that over and over again, telling the story of how my great great grandparents wentfrom the genocide to four different countries and then eventually a few generations later, America and that was a way for me to continue to be influenced by my history and to share it with others.

Then, at family reunions, I heard stories about the genocide, like how one of my great unclessurvived by his mom putting him in her pant leg and walking down the dock hoping that he wouldn’t cry so that he wouldn’t be killed like other babies at the time. I heard about how my mom’s side of the family helped build the Armenian community in Uruguay,and how my great great grandfather led orphans out of historic Armenia into Jerusalem and Syria.

Talking about the genocide, remembering these stories and striving for recognition of it has always been something important to me for reasons I couldn’t explain. One of the theories that I learned later in school that helped me put words to the feeling that I was having growing up is this term called ethical loneliness. Jill Stauffer, a philosopher, defines this as the experience of being abandoned by humanity, compounded by the injustice of being unheard. I think it appropriately describes what it feels like to be a community whose dignity has been denied and whose truth is denied over and over and over again by the perpetrator state.

That feeling can also be partly defined as indignation (a word I learned from Ms. Hastings during my SAT studying!). It’s having the open wound poked or poured salt into over and over again by the denial of the truth. And that denial of the reality I knew as true was motivating in a way. I wanted to help alleviate that sense of ethical loneliness, so I think the play and all of my human rights work since has stemmed from that.

When I was a freshman in college, I went to the Mgrublian Center for Human Rights at Claremont Mckenna College, and I asked if I could produce my play. And they said, “Absolutely. We’re going to help you do that.” I assumed that one day in my four years, when I was a senior, I would produce it. But they were so supportive and made it possible for me to produce my freshman year!

That year, I ended up working with the Mgrublian Center on other human rights issues too, and even helped them put on a play with survivors of human trafficking whohad written the play about their experience of being trafficked and were the actors in the play, which was so powerful.

Throughout my time with the Mgrublian Center across my four years of college I worked on asylum cases and edited and helped publish a memoir of the Armenian genocide. My interest in human rights led me to look beyond my community and to prevent genocide from happening anywhere else so that other communities can be spared the century of suffering Armenians have experienced.

SL: You’ve interviewed hundreds of Syrian Armenian refugees for your project Rerooted. Is there a certain story that has stood out to you?

AB: I love Rerooted. It’s been probably the most meaningful project I’ve worked on to date. There are a couple of stories that stand out, but every single person that I’ve interviewed has been resilient and inspiring in their own way.

One story stood out because of the unfortunate and extreme conditions that this family suffered and their resilience. Their kids were kidnapped by al-Nusra, a terrorist group. And the mother said, “I have to go get them.” And the father said, “No, you can’t, it’s not safe” but the mother said “No, you cannot stop me.I’m getting my kids.” Then she went and she saved them. And now they’re living all together. But that wasn’t even the end of it. Then they moved to another part of Syria and had bombs rain down on their house. And then they moved to another region where people had lied to them and tried to take advantage of their vulnerable situation. And then finally, when I met them, I think it was their fourth move. The strength and resiliency they still had energized me to keep going forward and working on these human rights issues. One of the goals of Rerooted is to ensure the harms faced by the Syrian Armenian community are documented and included in the justice efforts for Syria and this family’s story is a primary example of why this is so necessary

I can share a different story that’s also memorable because it upholds another aim of Rerooted—preserving the Syrian Armenian heritage, culture, and language. The Armenian that we speak in the diaspora outside of Armenia, Western Armenian, is considered an endangered language by UNESCO. In each Rerooted interview, we ask people to talk about their genocide story, their life in Syria and Armenia, and then their journey out of Syria and in a new country, all in Western Armenian.

So the story is: one woman said that when she was flying from Syria to Armenia, she saw Mr. Ararat, which is in historic Armenia, and she started crying on the plane from an overwhelming sense of emotion. And then what’s really beautiful to me also is that when she got to Armenia, when she would buy vegetables, she’d get them in a little plastic bag, and the bags would still have dirt in them, because they were fresh. And she’d said she’d always keep the dirt that was at the bottom of the bag because she thinks of her grandparents and how they longed for their homeland and would have done anything to be back on Armenian soil after the genocide.

SL: Rerooted not only documents Syrian-Armenians, but provides educational resources to discuss Syrian Armenian history with students. Why was this important for you to include and how do you feel such history should be introduced to younger audiences?

AB: Yes! Rerooted has lesson plans on our website. I believe in the power of stories and that the best way to learn is through personal stories. I think watching a play or reading Anne Frank is more impactful and memorable than reading a textbook about the Holocaust. When I was first looking into Syria, it was all statistics: four million refugees, this many displaced people, etc. Then, in the summer of 2016, there was a picture of a drowned Syrian 3 year old, Aylan Kurdi,washed onto the shores of Greece and a lot of people began talking about Syria after that. Images and personal connections invoke empathy.

With Rerooted, we wanted to capture personal stories to preserve the rich educational and cultural history and traditions of the Armenian community, but also in the name of justice, help people be moved to act. Preservation, education, and justice all go together. Education is a way for us to serve preservation and justice.

For middle and high school and college, we have lesson plans where teachers can use the testimonies to teach students about the war or about being a religious or ethnic minority in the Middle East. The lesson plans are a way to include the testimonies into a school curriculum, but there’s so many different ways to learn from them.

SL: You graduated from Harvard Law School with an astonishing 4000 pro bono hours. The requirement to graduate is 50 hours, so you did 80 times the requirement. Was it a goal to achieve a certain number of hours? What keeps you going when the work is pro bono and unrequired?

AB: No, I had no idea I did that many! I was just doing. I just like to do. I wanted to do as much as I could to help others and so every opportunity that would come up, I would say yes.

There was a war that broke out in 2020 between Armenian and Azerbaijan during the pandemic. I spent a lot of my time during the pandemic working for that cause. I got friends together from around the world to write reports to the United Nations about the conflict and the abuses Armenian people were facing. I did a lot of pro bono work for Rerooted and a lot of pro bono legal work through clinics and student practice organizations at school. One of my clinics ended in April, but I continued until June because I loved it so much and I got so much from it. I don’t think my days would be as meaningful if I were not doing this work to uphold human rights in one way or another.

SL: What really resonated with me about your work is your unrelenting hope. Was there something that instilled such steadfast character in you? And how can we all carry your optimism?

AB: That’s very sweet of you to say, thank you.

The best answer is the people I work with. They have so much hope. Most people I’ve worked with, such as asylum seekers, trafficking survivors, and survivors of mass atrocity, torture, and the Holocaust, have hope. And how can you not have hope when the people you work with have hope? You’d be doing a disservice if you didn’t share their hope.

SL: What can the average person do to become more cognizant of human rights issues globally and support endeavors like those you undertake?

AB: Generally, I might start with reading the annual reports from Human Rights Watch they publish about each country. If you want to learn more, that’s a condensed way to see different abuses happening in the world and then you can do more research into specific issues that stand out to you.

I think that once you find an issue you’re passionate about, try to find a local NGO working on that issue and reach out. I love cold emails. That was a huge part of all the opportunities I’ve had—I saw something that looked great and emailed asking how I could get involved. People tend to be surprised at how often people answer those, but they do!

If you have the time and ability, lend a helping hand and offer help to an organization you support. That can go a long way.

How you can help my work specifically: Rerooted takes interns! If someone at Great Neck South wants to work with Rerooted, please reach out and we can try to find a way for you to best help and learn.

SL: What advice would you give to high school students or anyone in the process of figuring out themselves and their future?

AB: My first piece of advice, which is really cliché, is to follow what you’re passionate about. Do what you enjoy and what brings you happiness. If you’re doing something you don’t like, stop doing it. There’s so much to learn now, in college, and beyond. Be curious and ask questions everywhere you go. Never write anything off as unimportant or uninteresting until you genuinely learn about it. Be exceptionally curious and never lose the thirst for learning.

Don’t be afraid to create things. Be innovative. You have so many ideas so go act on them. Find someone to support your ideas. When I wanted to write my play, Mr. Weinstein supported me, and when I wanted to put it on in college, the Human Rights Center supported me. All I did was ask them. I will pass on what my mom has said to me my whole life, “the worst they can say is no.”

Ask for help and ask to help. None of my achievements occurred in a vacuum or alone; . everything has been because I asked people to take a chance on me, either letting me help them with a project of theirs and learning from that and their patience, or letting me carry out my own project and growing from that, and you will find those people along your paths too.

SL: What are you working on now?

AB: We are working on a joint report with Harvard, Yale, and Wellesley College through an organization called the University Network for Human Rights to document violations from the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war. Further, for Rerooted, it’s our fifth year and we’re writing a five-year report about what we’ve accomplished. It should be on our website in the coming months!

SL: Thank you so much for speaking with me and thank you so much for your work. Is there anything else you would like to add?

AB: Thank you. Thank you to everyone at Great Neck South for a wonderful foundation and education. Nothing is possible without a supportive community and foundation and I count myself as extremely lucky to have had that at South.