We Must Celebrate Contemporary Poets of Color

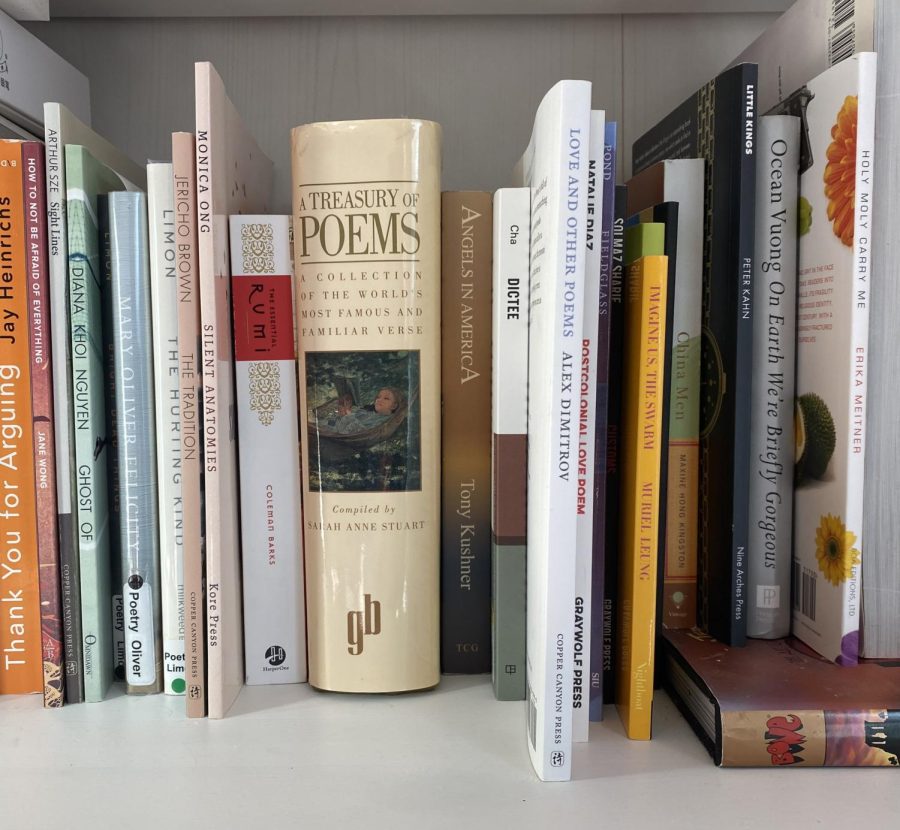

A bookshelf of contemporary poetry including Sight Lines by Arthur Sze, The Tradition by Jericho Brown, and The Hurting Kind by Ada Limon

March 25, 2023

Every June, as students slip into their summer slump, they receive their anticipated summer reading assignments. Seniors taking AP English Literature and Composition are expected to select and analyze one poem from a list of 32 options. In 2022, the list included only one poem by a living writer, two by writers of color, and three by female writers. That version was revised from 2021’s assignment, which included no poems by a living writer, two by writers of color, and one by a female writer.

As poetry is generally absent from ninth, tenth, and eleventh grade curriculums at Great Neck South, 12 AP may be the first time that many students deeply investigate poetry. Staring at a list that overwhelmingly included works by dead, white, and male poets, I felt the accustomed wave of disappointment. This list reminds my classmates who are less familiar with contemporary poetry and less inclined to read outside of school that poetry, that language, and that the world are dominated and defined by dead white men.

In the past few years, America has undergone a momentous racial reckoning, but the literature taught in schools remains as rigid as ever.

The Western literary canon, a body of work universally accepted as exemplary and foundational, is undeniably worthy of reading and analyzing, especially since modern authors often allude to works in it. But when the same names and faces repeat again and again and again, the canon restricts the abundance of newer or more experimental work, alienating and robbing us of a wider world.

Literary critic John Guillory argues that the canon creates a “cultural capital,” enforcing a social hierarchy about culture and civilization. Spending months every year studying Shakespeare’s plays, regardless of how culturally-influential they are, reinforces that Shakespeare merits more of our time, energy, and praise than any of the tens of thousands of living marginalized writers. Students absorb that Shakespeare, Dickens, Frost, and other dead straight white men occupy a standard of writing above all others and logically, may attempt to mimic their style. “In my early 20s,” poet No’u Revilla described, “I kept imitating dead white men because that’s what was put in front of me and I didn’t know how to reach for anything different. Representation matters.” Only when Revilla discovered poetry that reflected her Indigenous Hawaiian culture did she see poetry as a “closeness” and dedicate herself to writing “toward closeness.”

What’s more, many canonical pieces of literature assert outdated and troubling viewpoints. Charles Dickens, through his speeches, letters, and books, displayed anti-Indian, anti-Hindu, anti-Zulu, anti-Native American, anti-Italian, anti-Irish, and anti-Semitic sentiments. Even Slyvia Plath, known for her feminist writings, incorporated stereotypical descriptions of Mexican, Chinese, and African American characters in her novel The Bell Jar. Celebrating and canonizing these authors permits their beliefs to be swept under the rug, which is especially dangerous to young students. Adding to and adjusting the canon does not undermine the quality or significance of the established work, but spotlights works that are just as deserving.

Language is not sterile. It instructs perception and offers permission. Reading experimental work by Diana Khoi Nguyen, Don Mee Choi, and many other BIPOC poets instilled in me the belief that language is mine to maneuver and thrives outside of white-dominated spaces. They equipped me not only with the drive and fearlessness to create my art as I see fit, but also to live my life without deference to societal delineations.

Similarly, Vietnamese American author Ocean Vuong shares the liberation he felt from reading Japanese American poet Garett Hongo’s writing. “[Asian] voices—which are so often erased, silenced, crossed out, or stolen, suddenly reappear in Hongo’s poems—to stay,” Vuong writes. “As I read, I felt I was standing side by side with someone I might become. I felt the machetes come down, the green stalks falling. I felt I was making something of value with my bare hands.”

I didn’t know I could be a poet when I received my first publication, or even when I was awarded prize money. I knew when I read and met writers like Ocean Vuong, Muriel Leung, and Jane Wong—who look like me, who write about topics close to me, who have parents who look like mine. Who, in spite of everything, rose to the odds and defied stereotypes through their words. They illuminated that my experiences matter—that I matter.

Contemporary BIPOC poets including Lucille Clifton, Don Mee Choi, Jericho Brown, and countless others—who have invented their own forms and pushed the boundaries of writing—have moved and transformed the modern poetry scene significantly and similarly to Samuel Daniel or William Shakespeare in their respective time periods. I wholeheartedly believe that their works will likely become classics in the succeeding centuries. It would be an injustice to not study them now.

Even if contemporary poetry remains absent from structured English classes, it is easily accessible through the blossoming world of literary journals. ctrl+v publishes the most intriguing visual and collage poetry. Underblong publishes the most humorous poems. FIVES publishes the most innovative digital writing. The Rumpus publishes the most compelling selection of creative writing, essays, interviews, and columns. Smokelong Quarterly publishes the most visceral flash fiction in both English and Spanish. There is a perfect journal filled with wondrous writing for each one of us, wherever our interests lie.

If anything, reading work by contemporary poets of color is simply joyful. As poet Chen Chen says, “[Poetry] nourishes the heart…Like plums do. Like sunflowers. Like a good, long kiss in this brief, brief life.” In her poem, “won’t you celebrate with me,” Lucille Clifton proclaims, “come celebrate / with me that everyday / something has tried to kill me / and has failed.” In the face of systemic injustice, Clifton asks us, her readers, to join her with joy, with celebration. Let us celebrate with her.

Here is a non-exhaustive list of poets of color to check out:

Natalie Diaz

Jericho Brown

Shelley Wong

Marilyn Chin

Victoria Chang

Talin Tahajian

Luther Hughes

Yanyi

Diana Khoi Nguyen

Renia White

Claudia Rankine

Derrick Austin

Solmaz Sharif

Aracelis Girmay

Eduardo C. Corral

Rajiv Mohabir

Tarfia Faizullah